| |

|

|

from the issue of March 25, 2004

|

| |

|

|

| |

Museum gains visibility with Monks’ work

BY TOM HANCOCK, UNIVERSITY COMMUNICATIONS

Neale Monks believes it’s essential to bring the fruits of academic research to the public.

| |

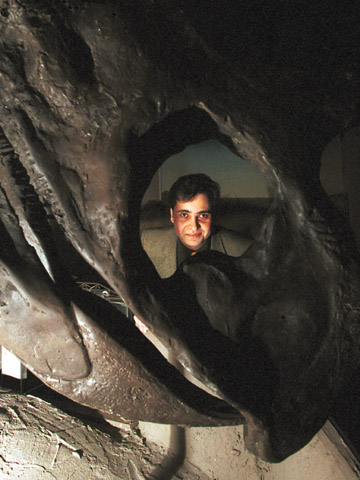

| | | Neale Monks, a visiting research professor at the University of Nebraska State Museum, is framed by the skull of a Chasmosaurus, a horned dinosaur closely related to the Triceratops, in the Mesozoic Gallery of the museum in Morrill Hall. Monks has been working to expand the outreach activities of the museum. Photo by Brett Hampton.

|

The UNL visiting research professor had initially planned to work at UNL on a marine invertebrate called the nautilus, a relative of the ammonite fossils commonly found in Nebraska, but thanks to a chance meeting with State Museum Director Priscilla Grew, he has gravitated toward science communication projects instead.

“Shortly after I became director of the State Museum in August 2003,” Grew said, “I got an e-mail from Neale offering to volunteer his assistance to the museum. I could hardly believe our good fortune. In fact, I had bought a copy of Neale’s book on ammonites at the Natural History Museum (in London) with no idea that he would be coming to Lincoln and offering to help us.”

“It’s just lucky that I’m here at this time,” Monks said. “Maybe I can transfer some of the programs that work so successfully at the Natural History Museum in London to work here in Lincoln. I’d like to see the State Museum become proactive about how it interacts with other institutions such as the Children’s Museum, the Folsom Children’s Zoo, art galleries and other museums around the state,” Monks said.

Monks took a big first step toward this goal when he recently put together the Dinosaur Detectives program at the Lincoln Children’s Museum. While the State Museum has offered dinosaur programs for school groups, this was the first collaborative program for the public to be offered by the State Museum and the Children’s Museum.

At the event, children were guided through a simulated fossil-gathering expedition. Monks and Kathy French of the State Museum devised the activities and recruited the staff. More than 1,400 attended.

“It’s the first of what I hope will be a program of similar activities bringing (the University of Nebraska State Museum) to the public in venues it isn’t normally seen in,” Monks said.

A native of England, Monks received his bachelor of science degree in marine biology and ecology in 1994 from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. He obtained his doctorate degree in 1998 while carrying out paleontological research at the Natural History Museum in London. That museum’s faculty had been seeking a marine biologist who would look at ammonite fossils in a fresh and different way, Monks said. The work was “basically an imagination exercise. They said, ‘Here are the fossils. We know nothing about them. Come back in three years and tell us what you think you have discovered,’” he said.

Monks performed experiments and published papers about ammonites but eventually realized that “about four people on the planet” cared about what he had written. That’s when he became interested in outreach. When he presented information in a popular format, he found an interested audience in natural history clubs, schools and television viewers.

“I did more good for the Natural History Museum by just talking to people in a light-hearted, easygoing way than through my papers,” Monks said.

“I think it’s important that a scientist reflects on why he is doing (research) and who’s paying for it. If what I am doing is never going to solve any of man’s great problems, the other way of looking at it is, ‘What can I do to make life a little more pleasant for those who just want to know a little more about the natural world?’”

Monks found that the public may not want to know the details about when an animal lived or the mathematical details of testing models in wind tunnels. But they would like to hear a story about what life was like 100 million years ago. And in a nation such as England where fossil collecting is a popular hobby, people were happy to see him on TV talking about how to find and identify fossils.

Monks’ outreach has included serving as an expert for the BBC’s Fossil Road Show, contributing material for other programs such as Survival Television, Green Umbrella and the Disney Channel, and co-writing the book Ammonites. Ammonites were similar to modern squids except they had a coiled, snail-like shell on their back. They died out at the same time as the dinosaurs, but their fossils are common and among the first fossils amateurs hunt for because they look so beautiful.

“The book has sold well and been read more often and more widely than my papers,” Monks said.

However, Monks acknowledged that several factors discourage many scientists from promoting their research. Scientists at universities put in long hours with classes to teach, grants to write, essays to grade and graduate students to supervise, so they have little time left over, for example, to go to an elementary school to deliver a presentation, he said. Those are legitimate priorities, Monks said, but if a university is going to be popular in the state, academics need to talk to constituents outside their usual circles.

“Academics should make themselves available and their supervisors should see that as contributing to the big picture,” Monks said. “You won’t see that on the bottom line of the department but it will make the university popular.”

Because the University of Nebraska system encompasses four universities, Monks said it becomes even more important that scientists here provide information on current issues to different constituencies, such as schools and the public. Scientists should work to ensure that Nebraskans appreciate that they live in a state with such natural wonders as the Sandhill cranes and a world-class fossil collection at the State Museum, he said.

“Nebraska is gifted in many different ways that aren’t always apparent,” he said.

Monks has helped the State Museum share these gifts with Lincoln students by visiting Humann Elementary School to talk about dinosaurs, a favorite subject among that age group. Two girls at the presentation even corrected his identification of two dinosaur models, Monks said.

Unfortunately, when those students become middle- and high-schoolers, the fun part of science often goes away, Monks said, and is replaced with calculations, measurements, test tubes, Bunsen burners and repetition.

“Wouldn’t it be nice for the museum and others to re-instill the interest and wonder of science to kids in middle school, when science becomes harder?” Monks asked. The key is to encourage students to hang in there, “because when you get to the university you get to do a lot of fun stuff,” he said.

“My work may not change the world,” Monks said, “but if I can inspire one of those kids to study science at a higher level, perhaps at UNL, maybe he or she will be the first person on Mars or be part of the team that finds a cure for cancer. Maybe the reason they follow a scientific career is because one time they went to the State Museum and someone there went out of his or her way to spend a bit of time encouraging them.”

GO TO: ISSUE OF MARCH 25

NEWS HEADLINES FOR MARCH 25

Museum gains visibility with Monks’ work

Grant to aid study of social issues of infertility

Parking offers options to combat shortfall

Activities abound at CASNR Week March 25-31

Convocations to honor students, faculty

Lecture to address change of Nazi policy in WWII

Moulton to give Nebraska Lecture March 30

Second construction company enters negotiations on North Stadium project

‘Transition to University’ report available

UNL High School students beat national scores

731665S33036X

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|